Aomori

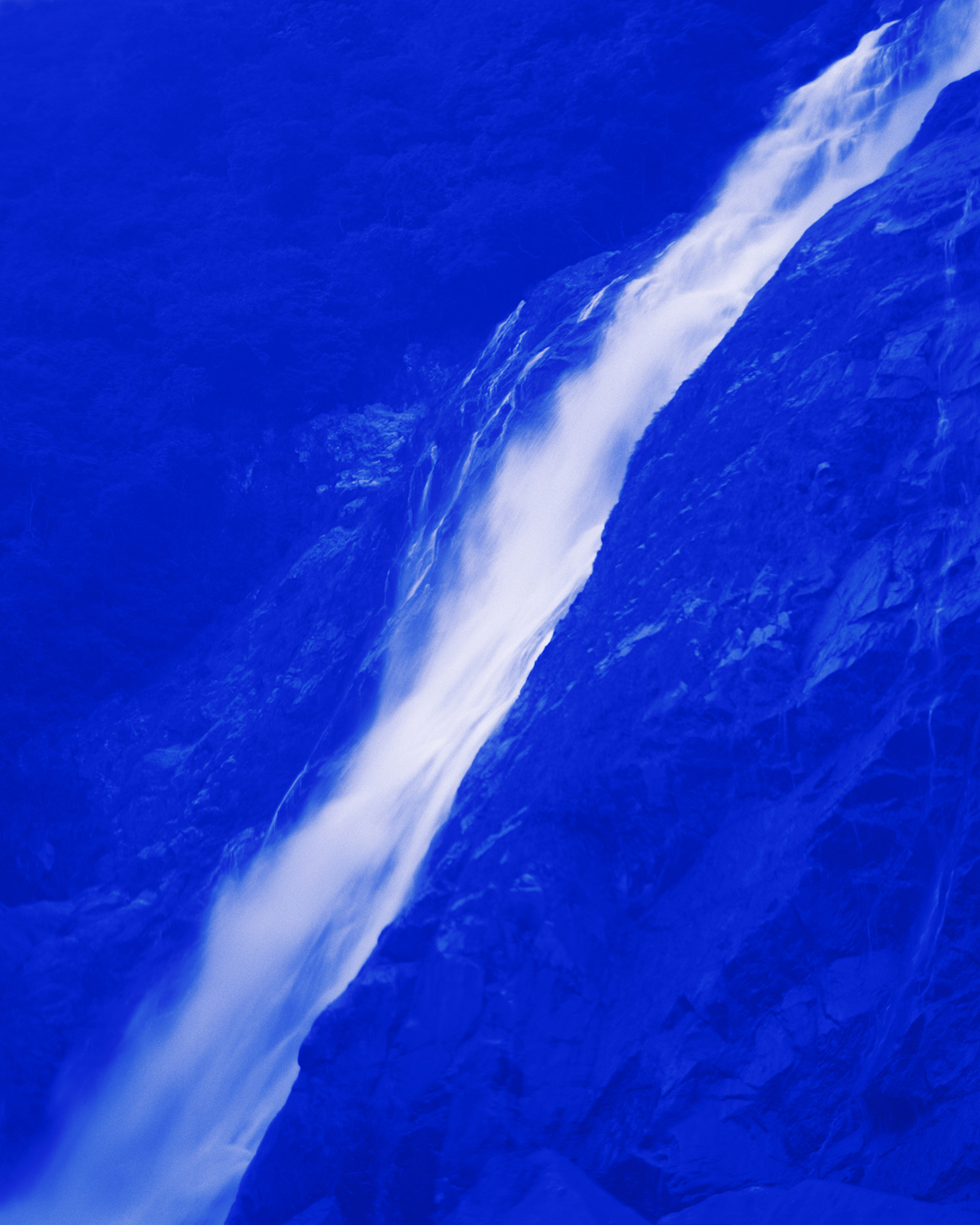

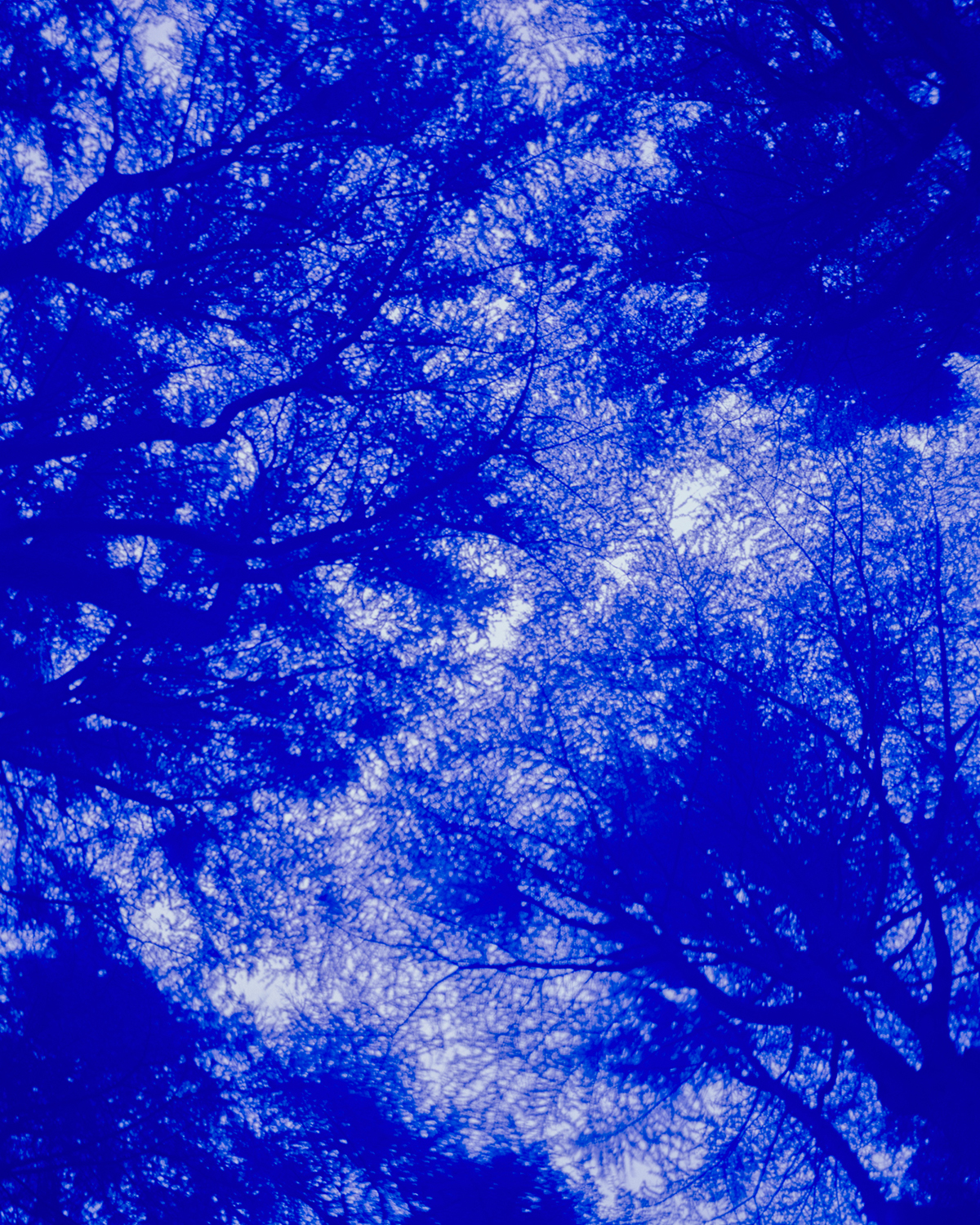

In Aomori, my interest was drawn, with an almost overpowering urge, towards the colour blue. The colour and its philosophical potential, recurs throughout art history, as seen in the work of Yves Klein, Hokusai, Derek Jarman and the writer, Rebecca Solnit; she muses on it in her seminal work, A Field Guide to Getting Lost:

“For many years, I have been moved by the blue at the far edge of what can be seen, that color of horizons, of remote mountain ranges, of anything far away. The color of that distance is the color of an emotion, the color of solitude and of desire, the color of there seen from here, the color of where you are not. And the color of where you can never go”.

For Solnit, the blue world embodies distances we can never quite arrive in. The colour blue —formed through fluctuating atmospheric conditions at distance—creates for her, and many others, a great immaterial and metaphorical plane. For me, the immensity found in the colour blue, also encouraged a deeper reflection on our past, present and future. I thought I’d utilise this energy to help question what the photograph is, and how it perhaps exists beyond a fixed time and place. Moreover, the work embraces potent ideas concerning time and Lichtung (a place where anything can appear), which draws on the writing of Martin Heidegger, and is conveyed through the subject matter of the forest. Aomori meaning “blue forest” in Japanese, synthesises these ideas, to create a psychologically charged environment.

Experimentally, I sourced blue glass from a church window, which was then cut to size to fit the filter holder of my camera. I wished to truly introduce this colour into my process, by exposing my film directly to the blue world. Glass, which is normally a material of separation, is employed directly in my process to unite both medium and idea. These photographs bring Solnit’s blue of distance near, into the world of the forest; they are by process, forever blue.

It was only later, when Susan Bright commented on the religious symbolism of my work, did I realise the importance of using this process in Japan, “the spiritual history of the process seeps through into the image, to a time when the land was a place of worship”.