Displacement – New Town No Town

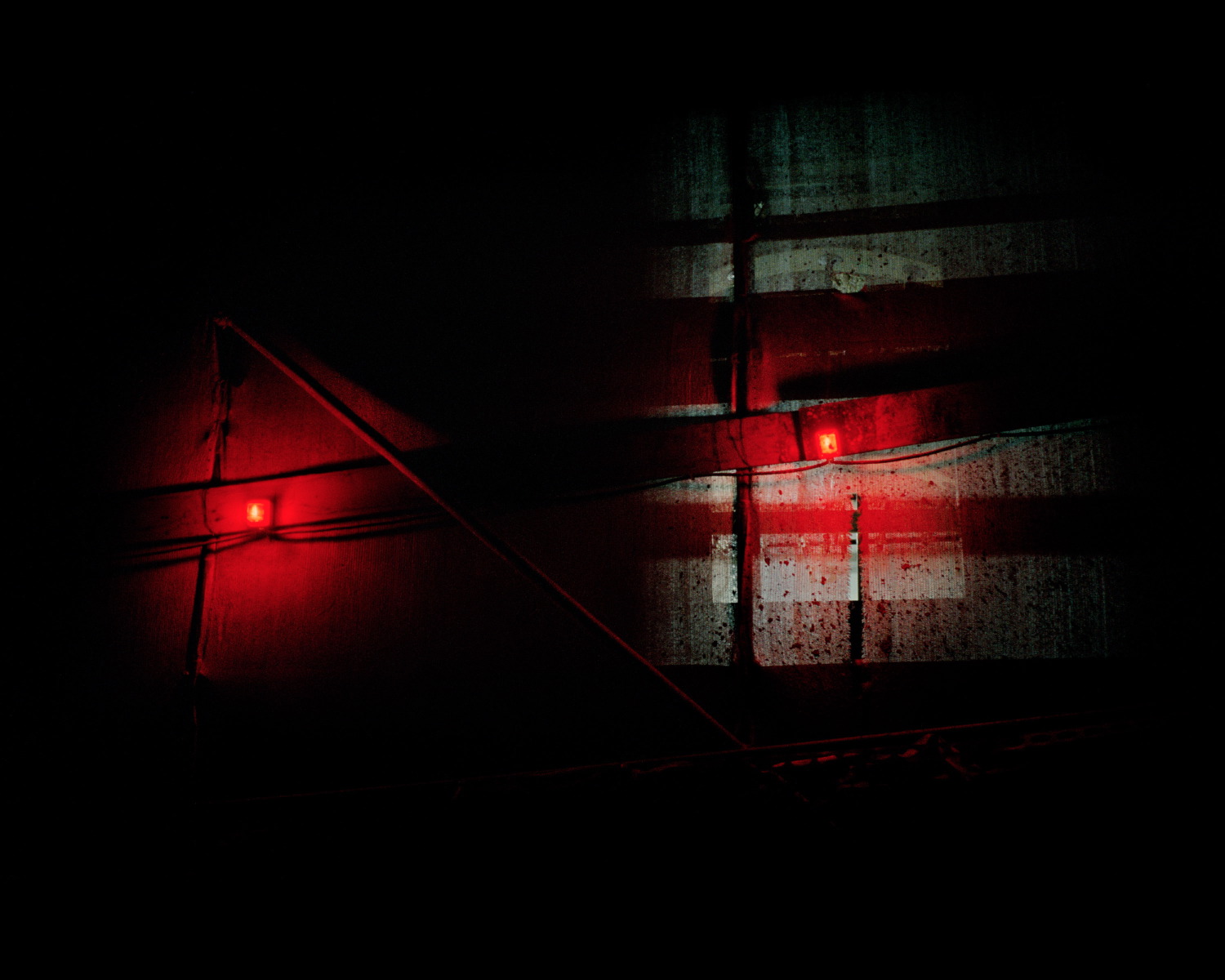

It’s the dead of night, and L’Aquila is shrouded in darkness.

We can’t hear anything. We can’t see anything. We are scared, but also slightly excited. It’s those houses, hollow, empty. Life rushes out coarsely, haphazardly, out of those bleak holes.

The darkness of an unlit city is thick, deeply sunk into the walls. It is unlike any other.

The loss of L’Aquila’s identity contributes to our feeling of displacement. The city is unrecognizable. Old streets have retained their names, but they are no longer what they used to be.

Never mind those street names, we say to ourselves. It’s where they lead to that matters now. After the great mass exodus, the displacement, the dispersion. We’ve become lost too.

Displacement is a journey through cities that change after being abandoned, lost to reconstruction. It’s a journey through loss without disappearance. The loss of the city-body, which we don’t want to grieve, but rather recover in the ways a community spontaneously rebuilds a sense of intimacy with its own surroundings.

We came to L’Aquila to recount the city’s new life after it lost its historic centre, and its inhabitants were relocated to the outskirts. We found a city made up of empty streets, new properties on sale, old buildings reemerging from the ruins as hotels, banks or shops, whose population lives in the remote New Towns, a suburbia of dormitories where shopping centres have replaced the old piazzas.

The result is a cartography of change, where images strive to delicately and intimately approach the abandoned and almost disarticulated city. Here, what seems peripheral becomes central, and disorientation is tangible, as in other suburbs around the world: inside and outside overlap, blend into each other and fade in the dark. The same darkness where souls search for themselves and for each other.