Daria Tuminas is a curator at FOTODOK. Between 2017 and 2019, Tuminas worked as the head of Unseen Book Market at Unseen Amsterdam. She obtained a master’s in folklore and mythology at Saint Petersburg State University, Saint Petersburg, and a master’s in film and photographic studies at Leiden University, Leiden. Tuminas regularly contributes texts to various media including: in 2017 she was the guest editor of The Photobook Review #12 published by Aperture; in 2018 she contributed a chapter on Eastern European photobooks to How We See: Photobooks by Women by 10 x 10 Photobooks; in 2020 she co-wrote a text Is a Book Worth a Tree? for YET issue 12 and co-edited doc! photo magazine issue 46; in 2021 she contributed an essay Oil & Moss for Foam Magazine #58:Talent.

Let's start with a commonly asked question. Tell us how your journey in the photography field started

I studied at Saint Petersburg State University at the Faculty of Philology, where I studied folkloristics (Folklore studies). Together with the Propp Center heads and other students/coeds I regularly went on expeditions to the Vologda and Arkhangelsk regions. At some point back then, I bought a used film camera and started shooting during these trips, and also everything outside of them. I wrote my dissertations (Specialist and Master's) about photography: the first, about the use of the canons of amateur photography in visual anthropology, the second about the so-called "photo frames'' - collages from family photographs that the informants placed in the space of the house. During 2008-2010 I also studied photography at the Yu.A. Galperin Faculty of Photojournalism of the St. Petersburg Union of Journalists. I also worked on texts about photography for various magazines and made some first steps in organizational work. I became more and more interested in the discourse of photography and contemporary visual art. In 2010, I entered the Leiden University Master's program in "Film and Photographic Studies”, where the main focus was the theory and history of photography, cinema and media. It was a moment of conscious choice for the formation of my professional future.

You work a lot as an independent curator and implement interesting projects. How may you define the word “curator” and what does it mean to you?

For me, being a curator means reflecting and deciding what form a project will take. The idea of multiplatform is also close to me. That is, most often there is a need to create not one form, but several at once and on different platforms: an exhibition in a physical space, an online educational program, additional theoretical materials in a publication, and so on. This is important for diversification, empowering different audiences to find the points of contact they need with the project through communication channels that are convenient for them. And, of course, it is very interesting to do this from a conceptual point of view: each new element or platform should not repeat the previous one, but complement it, while having its own value and integrity.

Perhaps an unexpected example of an interesting curatorial platform that I practice is work with the press. In the context of the seven-month COVID-19 lockdown in the Netherlands in 2020-2021, it was especially important to create additional spaces for thinking about projects. I invited interesting authors to write long-reads about projects (for example, Natasha Christie's text for Trigger); collaborated with the media, where we could discuss the works in depth (for example, ARCHIVO published a series of five research interviews with the artists of the exhibition). That which happens on the (online) pages of magazines can also become a space for creating meanings and a curatorial “challenge”.

From a practical point of view, a curator can solve very different tasks, it all depends on the context of the work: for which institution the project is being implemented, which team is involved with what skills, and so on. I work in the exhibition space FOTODOK (Utrecht) and we have a relatively small team, so I have many tasks. I organize exhibitions, some public events, publications, as well as project and structural fundraising, monitor communication on my projects, build the artistic program of the institution and develop interesting partnerships. Much of this is done, of course, in dialogue with the team. The curatorial work is based on communication with artists, monitoring their processes and project development, negotiating the presentation of works, cooperation with a designer on the visual identity of the project, writing texts, and supervision of production. Research, understanding of the ongoing processes in society and art and the formulation of one's own interests, questions and statements frames all other processes. For me personally, it is still very important that artists feel my support, attention and involvement. To summarize, the word “curator” means both a profession, and a way of life and thinking.

A Garden Revisioned. Installation from Pass It On. Private Stories, Public Histories, FOTODOK (Utrecht). Photographic Fragments — Studio Hans Wilschut

Tell us, do you have "favorites" among your projects? Perhaps some projects were especially difficult, and you are especially pleased with the form they eventually took.

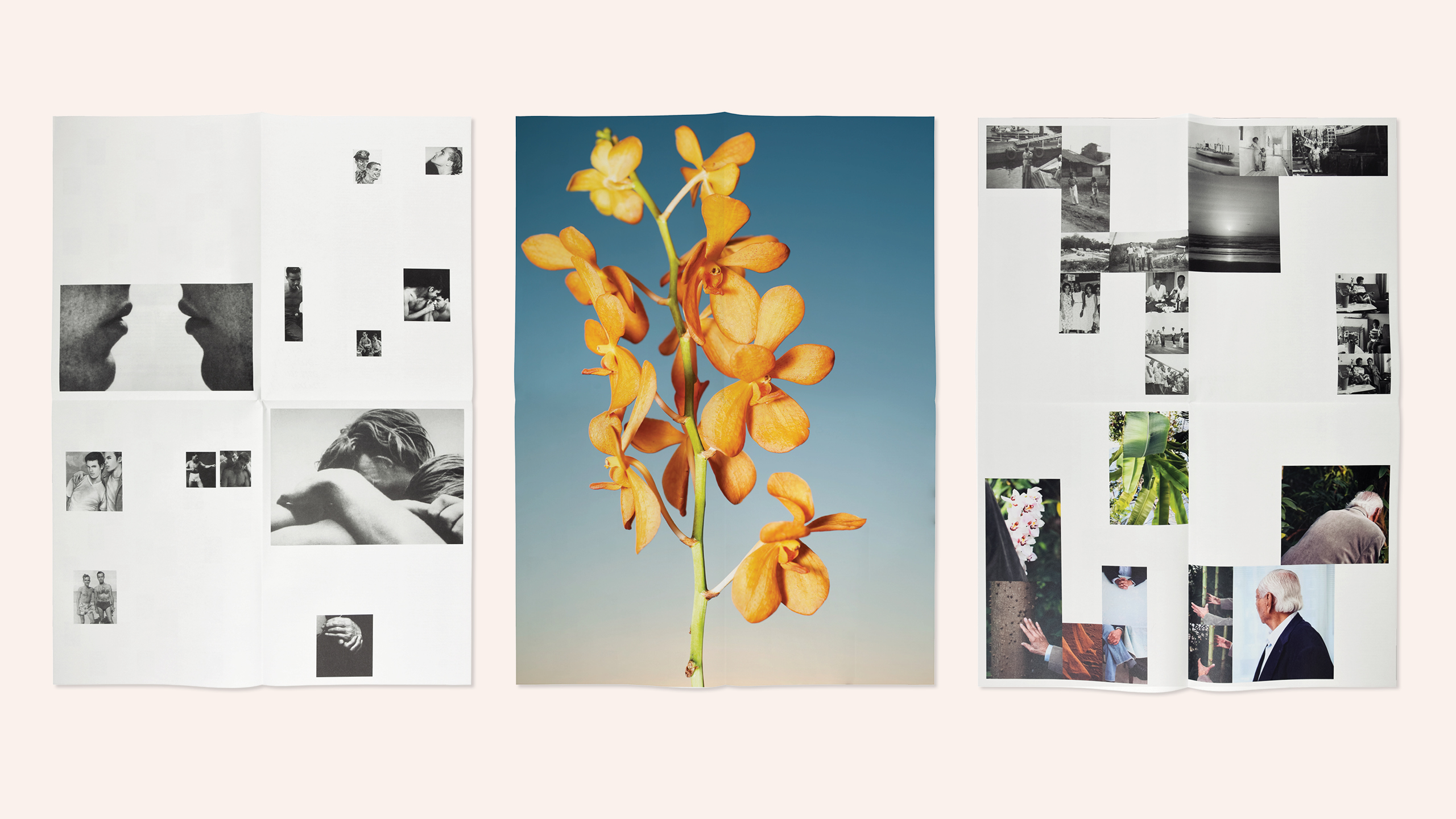

I definitely don’t have “favorites”, since each project is interesting and important in its own way. I'll tell you about "Pass It On. Private Stories, Public Histories", as it took place during a very difficult period of the pandemic and long-term lockdowns. It consisted of a group exhibition (November 27, 2020–February 28, 2021); 360° virtual tour; photobooks - the so-called "exhibitions in a box"; about 15 long-reads in the press; one-on-one meetings with artists in the exhibition space; four meetings between artists and experts from other fields, we call these evenings “Taferelen”; as well as the presentation of works in a public space, on the square next to the Utrecht Archives. The project was attended by Inge Meijer, Lebohang Kganye, Marianne Ingleby, Pablo Lerma and Yara Jimmink.

All of these artists’ work started with a specific family archive or the idea of a family archive and talked about how private stories can be the key to understanding larger historical narratives and their gaps. Thus, "Ho thubeha ha lebone" (Breaking Light) by Lebohan Kanye is based on photographs and oral narratives about her grandparents during apartheid (racial segregation policy in South Africa in 1948-1994), which the author meticulously collected, meeting with relatives, scattered throughout the Free State. Yara Jammink's project “When Summer Turned to Winter’ tells the story of the migration of the artist's grandparents from Indonesia to Holland in the early 1960s, as well as Yara's search for her roots and her own identity. Pablo Lerma, for the “It Doesn't End with Images” project, worked with the IHLIA LGBTI Heritage collection (the largest archive of queer culture in Europe) through which he tried to construct a potential archive of queer families that is missing from the history of photography. Marianne Ingelby in ‘Operation Detachment’ worked through the archives of her grandfather, who in 1945 was a US Army photographer in Iwo Jima and left behind a huge box of photographs and films in the attic of the house. Inge Maier's "A garden revised" investigates the story of a six-story wedding center in Gwangju that hosted 200 weekend weddings in its prime and then went bankrupt. The artist ended up at the art residence a couple of weeks before the demolition of the building and accidentally found an archive of films and photographs with pre-wedding shoots in it. All these projects were not completed yet, and it was important for me, on the one hand, to support the artists whose work was developing, and, on the other hand, to show the exhibition space as flexible and lively, in which the emphasis is on the process and experimentation.

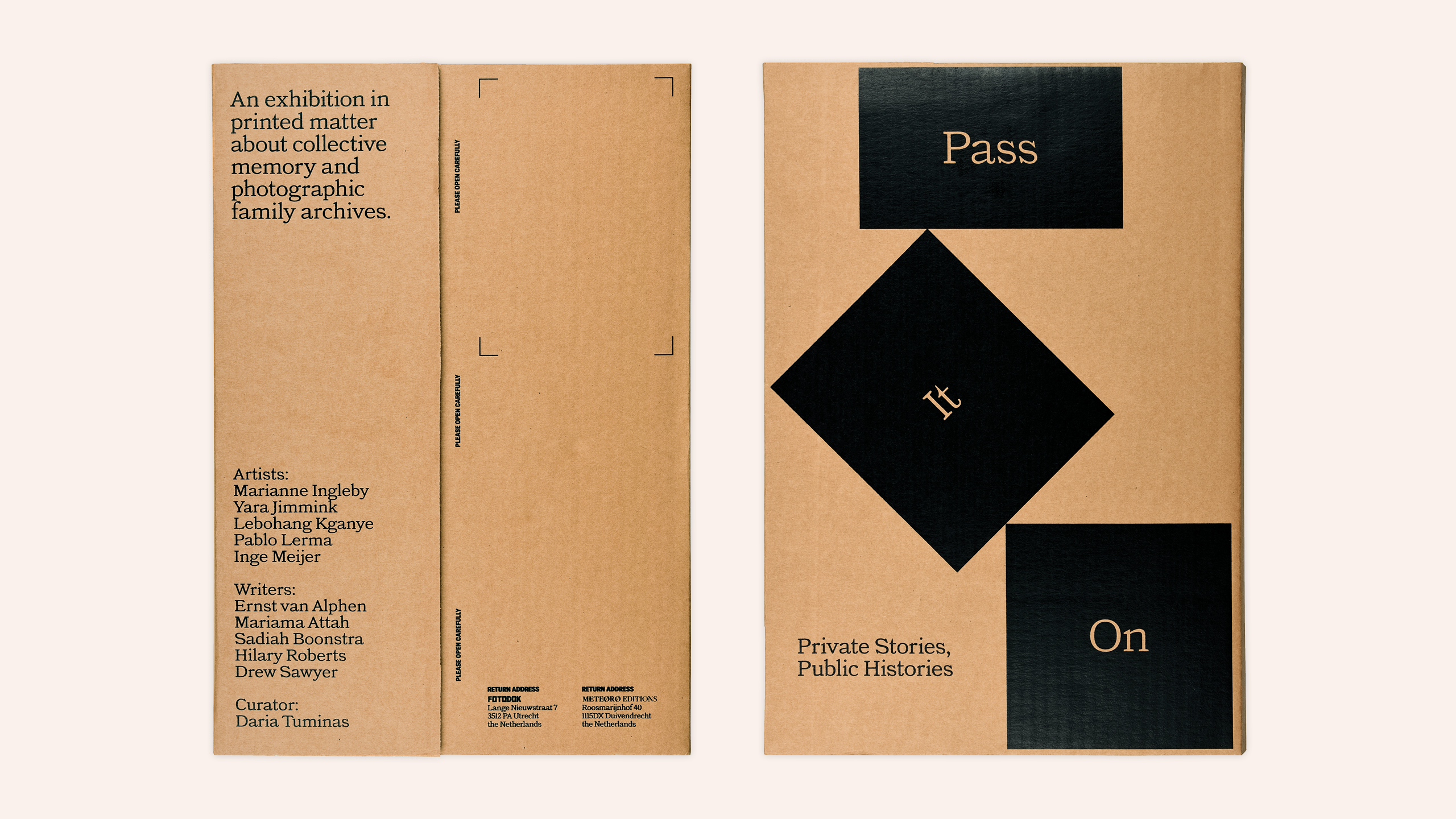

No project is complete without some difficulties or unforeseen circumstances. In the case of "Pass It On. Private Stories, Public Histories” it was, first of all, a lockdown that closed our space after three weeks of the exhibition and lasted until its end. We envisaged a temporary lockdown scenario, but did not think that it would last for nearly seven months. Nevertheless, we planned in advance to work on the publication, the “exhibition in a box”. In case it was not possible to visit the exhibition, it was possible to order a publication and host the exhibition at home. The publication, made in collaboration with METEØRØ EDITIONS and designed by Kummer & Herrman, consisted of a set of posters, research texts about the work, and each copy included one print by one of the five authors. The edition was not bound, as it was assumed that the images could be hung. However, in order to keep the whole content together, we decided to use the regular Raja box to ship the books, which became its cover, container, and packaging at the same time. An additional motive for this decision was the reduction of waste production. I'm glad how the project turned out to be in the form of a publication, and as a curator I was able to experiment with printed matter as an exhibition form. It was very pleasing that the publication ended up in a Special Mention on the shortlist for the 2021 Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards.

I am also very pleased with the virtual tour, which was able to include a variety of materials: video performances from artists, downloadable PDF posters, audio works, installation details, texts and much more. From it you can make a fairly detailed impression of the exhibition.

Pass It On. Private Stories, Public Histories. Design: Kummer & Herrman

Pass It On. Private Stories, Public Histories. Design: Kummer & Herrman

You are the curator of FOTODOK (Utrecht, Netherlands), whose program was dedicated to the theme of collective memory in the times of 2019-2020, and the series of exhibitions ended with the project “Pass It On. Private Stories, Public Histories". Why, in your opinion, does the theme of collective memory in the field of contemporary art always remain relevant and inexhaustible?

FOTODOK usually chooses one socially important topic per year and organizes a number of events and exhibitions that could explore it from different angles. We started working with the theme of collective memory from the exhibition “Joint Memory. Photographic Fragments”, which reflected on how the medium of photography constructs collective memory. Then we continued with the "This Creaking Floor and All the Ceilings Below" project. It was a collaboration with our neighbors Casco Art Institute: Working for the Commons. We invited the artist Bart Lunenburg to do a site-specific study of the building where our institutions are located. We wanted to question the collective memory of our own space, which was a monastery (later, a school). Without a discussion of artistic practices that work with archival materials, it would be impossible to talk about collective memory, so we organized “Pass It On. Private Stories, Public Histories”, which I mentioned above.

Collective memory began to be actively studied and discussed after the Second World War. In the modern era, the focus was on the future, but in the second half of the twentieth century, there was an urgent need to look at the past and rethink it, especially in regards to colonialism and the Holocaust. An interest in collective memory is an interest in how individual memory is formed through narratives, rituals, images, which are always created by other people. This is a conversation about the constructed nature of any memories and, accordingly, pictures of the world, as well as the role of the media in the manipulation of these memories. About the nature of a story that focuses on some topics to the exclusion of others. This is a conversation about trans-generational trauma.

Artistic practice is one of the best critical tools for dismantling and demonstrating the construction of collective memory, its myths, and its gaps. An opportunity to critically or therapeutically look at "yourself" - the space in which you live or work, the land on which you are, your past, your identity, your traumas. It is also an opportunity to bring to the surface narratives that have purposely or accidentally fallen into the shadows. Many tragic events, unfortunately, have not yet been fully comprehended and the necessary changes in society have not been carried out. This means that the tragedies of the past are relevant in the present and have consequences in people's daily lives. Everything related to the collective memory "hurts" here and now. Therefore, appealing to various aspects of collective memory in art is always relevant.

Joint Memory. Photographic Fragments — Studio Hans Wilschut

This Creaking Floor and All the Ceilings Below — Bart Lunenburg

This Creaking Floor and All the Ceilings Below — Bart Lunenburg

An exhibition planned in advance often changes at the time of installation, unpredictability makes its own adjustments to the original plan. Do you have a similar experience in your curatorial activity, when external circumstances or limited opportunities did not allow you to do what you had planned? What skills should a curator have to “stand on the raft” in times of crisis?

As a rule, the project is not modified at the time of installation, but rather gradually, so that all adjustments are made throughout the course of work. Usually one project is from half a year to a year and a half of work (a part-time work week, since work is going on in parallel with several projects), and during this time you can prepare for it in sufficient detail. I don’t remember a single case in which I had to change something fundamental during the build up. I try to make a 3D layout of space and arrangement of objects and works in SketchUp. But on the spot, some designs can still look or feel a little different, so of course, this is the moment when you need to be flexible and look on a case-by-case basis, where it is important to stick to the plan, and where you need to adjust it a little. Also, artists work in different ways: some have a very detailed technical description of the installation, while others prefer to leave a little “air” and make intuitive changes at the time of installing. It is important to feel what dynamics someone has and what the nature of the artistic process is, and, on the one hand, to offer your own methods, but on the other hand, to capture what is important and organic for the people with whom you work.

Sometimes there are "surprises": the light did not fit, something was printed incorrectly. But I usually don’t feel a big crisis, since everything can be solved one way or another: call and politely agree to do something or redo it urgently. Skills that help to “stand on the raft”: the ability to breathe, support colleagues, joke, call the contractors and persons involved, communicate the situation with the right approach, find out the possible options for resolving the issue and decide which of these options will be the most appropriate.

Pass It On. Private Stories, Public Histories. Photographic Fragments — Studio Hans Wilschut

Working on a collective exhibition is different from working on someone else's personal exhibition. At the least, it is because different tasks are set - to show the project and the creative path of one, or competently combine different authors and their stories into a single organism. What formats do you enjoy working with the most? How much do you interact with the authors while working on the exposition? How much can their personal vision influence your concept, or can you find a compromise?

In FOTODOK, we mainly work with collective thematic exhibitions, in which I try to introduce some experimental elements whenever possible. For example, combining an exhibition space with a studio space or working with site-specific projects. Both formats provide an opportunity to do interesting research, help artists in the process and actively interact with them. I try to be in dialogue with artists as much as possible, but the amount of time spent together is determined by necessity and geography - whether we have the opportunity to meet in physical space.

First, I have to learn as much as possible about the project. This information in itself contributes to the formation of a curatorial concept, which is built gradually: first it is some kind of question and interest, then research and communication with the author(s) begins, and already in this process of communication, a more concrete vision is polished step by step. It's a fairly organic process.

At this stage, we do not adapt or bring existing exhibitions, do not make large monographic, art-historical and trans-historical exhibitions. But I certainly would love to work with these formats. I hope that with the move to the new large Machinerie building at the end of 2023, we will expand our repertoire. It will even become a necessity, since we will build the program for 12 months, now it is 6. So far we have time for thematic research exhibitions, but their preparation takes a lot of time. In order to keep up with the program, designed for the duration of the whole year, you need to combine formats.

Joint Memory. Photographic Fragments — Studio Hans Wilschut

You are currently preparing an exhibition about different mental states. The topic is quite relevant, especially now, when people gradually cease to be afraid to talk about their problems, and they begin to pay attention to them, more than before, and this is very cool. Tell us more about the exhibition?

We are preparing to open the "Part of Me… Shaping Mental Spaces" exhibition in August 2022. Some of the artists involved that I can name are Marvel Harris, Irene Antonia Diane Reece, Peggy van Mosselaar, Outsiderland and others. Most of the participants live and work in Holland (since it was important for us to support the local art community), except for Irene Reece, with whom we will be doing an online art residence. There will also be a set-light solo exhibition by Mafalda Rakoš in the center, serving as a prerequisite as well as support of specialists working in the field of psychiatry Astare. As a catalog of sorts, we will co-publish the next issue of doc photography magazine!, as well as planning a public program and, traditionally, an online tour.

All presented projects are very personal stories that concern the authors themselves or their immediate families. These are stories of the experience of living with different mental states - from depression to dementia. We want to talk about something that is close and important to many, but around which there is still stigma and discrimination. FOTODOK focuses on socially important topics. When defining these topics, we think of society as macro and micro structures and always check with ourselves: what is our team thinking about? What are the stories that resonate with her? What life situations do we find ourselves in? This exhibition is personal and important not only for the artists, but also for our team, and we hope that it will be the same for the visitors - a space where you can talk openly and safely about your own experience. We will gradually publish information about the project and work on our social networks.

What parting word can you give to our readers who are at the beginning of their creative path?

“Parting words” will be said on my part by the Tik-Toks of the artist working with photography, Anastasia Bogomolova - right there is everything that you need to know for those who are at the beginning of their creative path.

*We interviewed Daria before the events of February 24

Daria Tuminas website

Natasha Christie's text for Trigger

360° virtual tour. Pass It On. Private Stories, Public Histories

Virtual tour. Joint Memory. Photographic Fragments

Tik-Toks of the artist Anastasia Bogomolova