As an art historian, I am particularly engaged in taboo topics, the reflection on traumatic experience and female art. Thinking about the transformation of the private into the public, I draw a speculative historical line from the Romantic era to the present day on the basis of an idea that any public manifestation has as its ultimate foundation a personal impulse, a viewpoint, a practical of theoretical experience.

The private and public aspects of a person’s life have been strictly separated starting from the antiquity. The private was personal, intimate, closed from the outsiders. The public, on contrary, was happening in the presence of society, therefore being open. The distinction between the private and the public for ages has been dictating the social morality, restricting the freedom of speech and artistic expression: for example, forbidding the display of certain emotions in public space. At the same time the impulse inducing the creation of an artwork is always personal, even in case of a commission. Since the personal perspective of an artist transforms into what he/she creates regardless of the presence and the type of the reward, the personal beginning is constantly present in any artistic expression. Invisibly present in public life, the personal has been episodically arising in the art of Antiquity (the famous erotic frescoes of Pompeii and Herculaneum), Renaissance (Dante’s Divine Comedy) and the turn of the 18th and the beginning of 19th century, especially vividly shining through in the art of German romantics – philosophers, writers, artists and composers – who gave birth to the myth of the genius which defined the human-centered pictureof the world, governing the 19th-20th centuries.

The focus on perceiving a human being as an autonomous individual, a creator who has no power over him, has given an existential direction to the philosophical enquiry. Existentialism, the philosophy of human existence, the foundations of which were set by the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard in the 1840s, has found its followers on the eve of the World War I in the Russian Empire (Nikolai Berdyaev, Lev Shestov), after that in Germany (Martin Heidegger, Karl Jaspers), after World War II in France (Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Albert Camus, Jean-Paul Sartre), and numerous predecessors among the antique philosophers, German romantics, Russian classicists, etc. Kierkegaard started speaking about purely personal matters such as the uniqueness of the human experience, the value of experience itself, fear and sexuality; having opened the private sphere of life to the public discussion. A century later the French existentialists Camus and Sartre have created a series of fictional texts exploring the existential triad: fear, despair, hopelessness. Their key works, among which ‘The Stranger’ and ‘The Plague’ by Camus and ‘Nausea’ and ‘The Wall’ by Sartre, raise the thorny issue of inner and outer freedom, choice and alienation. A performance as an artistic practice which conceptualizes space, time, body and the relationship between the artist and the viewer represents an illustrative example of the transformation of the private (often intimate) into the public. Through the physical expression of an act unpredictable for the viewer, the performance is curious for observing and convenient for analyzing. Apart from that, speaking about transformation of the private into the public is impossible without examples, therefore I am going to let myself next give a number of those most significant in the development of the performance.

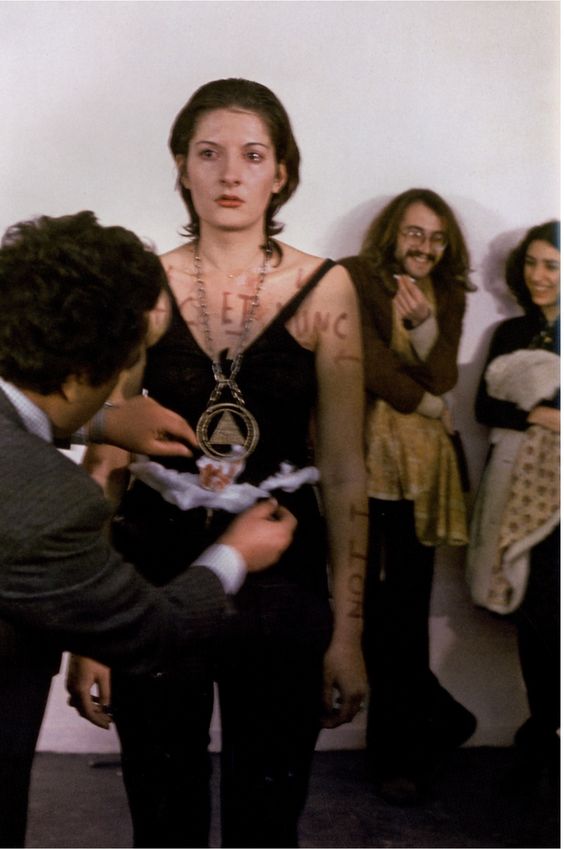

Marina Abramovich / Rhythm 0 / 1974

Yoko Ono in her famous work Cut Piece, first performed in the Sogetsu Art Center in Tokyo in 1964, suggested the spectators to cut with scissors a piece of any size and shape at any place on her dress. This way the public got unlimited access to the artist’s personal space, the power over her clothes and body. Later in 1974 Marina Abramović held a similar performance Rhythm 0 in Naples: the artist willingly put herself in the hands of the public, giving them not only the complete freedom of action, but also 72 objects including a loaded gun. Both projects erased the border between the private and the public, exposing the objectification of female body and the raw wildness of a human who has the right of violence with impunity.

The art of second-wave feminism was actively using the form of performance which ideally illustrated the argument ‘The personal is political’. The personal often had a form of a female body, even more ostentatiously than in works of Ono and Abramović. In 1968 in the middle of a film festival an Austrian artist Valie Export held the performance Tapp-und-Tast-Kino (Tap and Touch Cinema) during which the viewers could touch the naked body of the artist which was put in a box shaped as a screen with a cutout in her breasts. This way the artist criticized the objectification of female body in cinema.

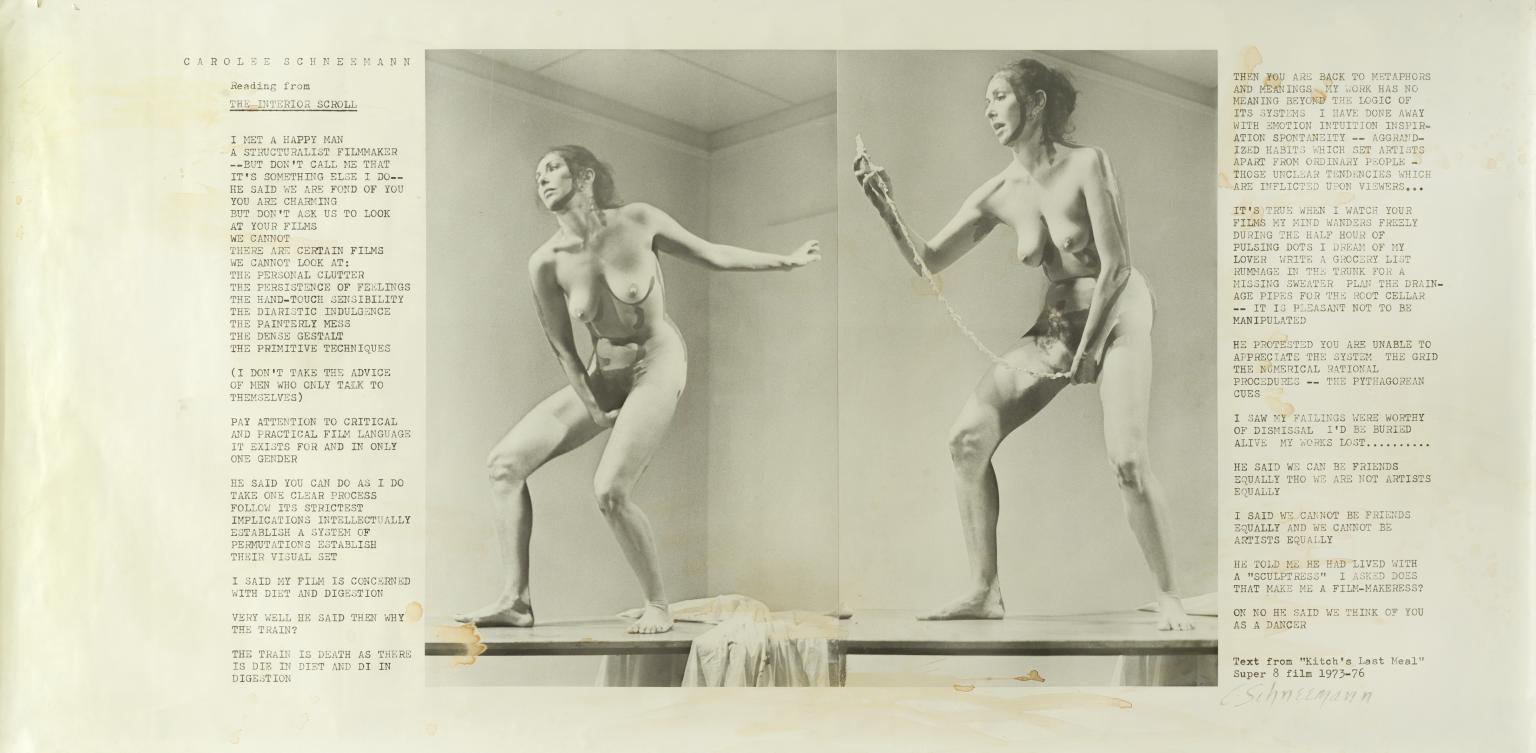

Lea Lublin in the work Mon fils (My son) in 1968, performed at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, transformed the intimate and at the same time routine practice of childcare into a performance, trying to equate the motherhood and an artistic and political statement. In a different way the ‘purpose of a woman’ was conceptualized in Judy Chicago’s Birth Trinity (1972), during which the 25 female participants of the performance imitated the process of giving birth, accompanied by the ‘contractions’, wild screams and eventually cradling the newborn. One the brightest performance on the topic of female body and sexuality is the work of Carolee Schneemann Interior Scroll (1975), during which the naked artist in front of the audience took out from her vagina and read out loud a scroll with a speech about the transformation of a woman from a model - an object, into an artist – a creator. Apart from performance tightly connected with corporeality, one can also point out existential performance exploring the cruelty and primitive animalistic states of the human. This type is represented in many works of Marina Abramović, such as Balkan Baroque (1997) and the aforementioned Rhythm 0. A key work standing on the point between performance and video art is the Violent Incident: Man-Woman Segment by Bruce Nauman (1986). In a cycled but unsynchronized record on twelve screens two people play a scene in a restaurant: a man offers a chair to a woman and then pulls it away when she is sitting down so that she falls; they start an argument with fighting, and then the characters trade places. The mutual misunderstanding, ineptitude to come to peace and the inability to stop, evolved into the ping-pong of resentment, raise attention to the hidden in the depth of intimate experience problem of violence taken out into public space by the means of artistic creation.

Man-Woman Segment by Bruce Nauman (1986)

Thus, in 20th century the personal deliberately seeks the exit into public space by the means of exposure of soul-searching in literature and the bodily practices in modern art. In the feminist discourse the personal transform into political, while the political is essentially public. Over time the strict distinction between the private and the public stops being the only possible reality, and the transformation of the private into the public becomes a certain catalyst of humanity in the artwork. In our time sincerity acquires the right of the supreme value, it provides focus to the trueness – something lacking in the human in a world where the public is often associated with hypocrisy and sham; while the personal, on contrary, has the unique ability to touch a raw nerve, raise attention to the acute social problems and embrace empathy.

Aglaya Zhdanova

Translated by Ekaterina Torubarova

Carolie Schneeman / Inside Whistle / 1975