Artur Bondar is a photographer, publisher, collector from Ukraine. Author of seven books, such as - "Shadows of the Star Wormwood", "Signs of War", "Barricade", "Valery Faminsky V. 1945", "Edge" and others. Currently he lives in Moscow and continues to work on personal projects on the topic history, difficult heritage, private and collective memory.

The topic of memory is important in global sense and probably for someone personally. Why is it important for you to make projects related to memory?

It is important to mention that I have been creating my projects during my development in photography, and the first project about war veterans ‘The Signatures of War’ appeared when I had just started creating individual projects. Back then one of my two grandmothers died two years before the start of the project, but the thought of not having asked her what I could ask and not having learnt what I could learn was not leaving my mind. Moreover, when I was working in an agency, we were all the time shooting memorial ceremonies, parades and so on – the places where you notice veterans more than usual. There you can see the real veterans, the witnesses of war, who leave us very quickly. These two points inspired me to create that project back then.

Taking the next project ‘Shadows Stars Sagebrush’, it was the anniversary of Chernobyl catastrophe, where I went by a chance. For the project about the military town (‘Where my childhood died’) I had again a personal reason. I returned home to where I had grown up, and saw that everything had changed, because I have not been there for a long time. More precisely, it had changed so much that everything I remembered was left only in my memories. The same is about other projects – I don’t plan them, they just somehow happen.

Currently I’m working on a project about the search teams which look for the soldiers gone missing during World War II. Once I went for a search party, I looked at it and wanted to understand what it is and how it is done. First of all, I was inspired by the people who do it.

I cannot say that the topic of memory is important for many – I made these projects because in the first place they were important for me in that moment. I am very lucky – I do what I like and enjoy my projects, so I don’t have the need to follow someone’s rules.

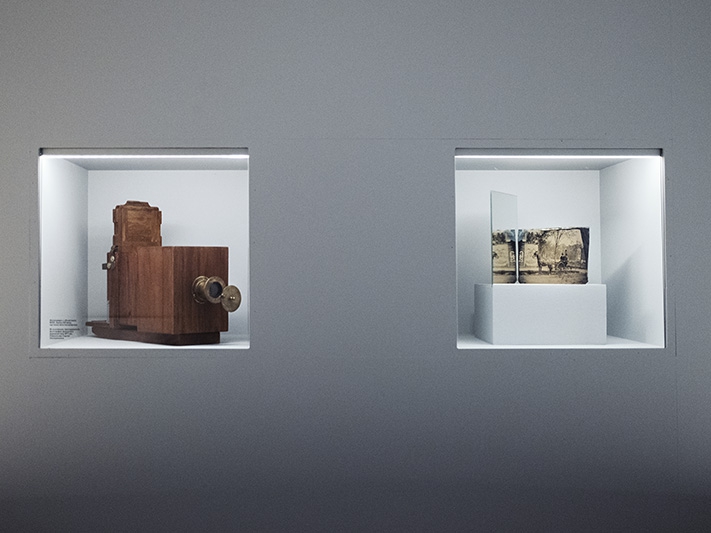

Recently you opened an exhibition ‘American Tintype’. Tell us about it. Where did you find the images and how did it all come to reality? In general, how do you work with an archive?

In 2014 Oksana Yushko and I went to a residency in the American south, to Paducah, Kentucky. This town is literally as the expression says, in the middle of nowhere. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Ohio and Tennessee, known for the floods destroying local old Victorian buildings. Later a dam was built in Paducah to prevent the floods, but the buildings were left unrepaired, and the people abandoned them. After that they created a program in which the artists could buy these houses for 1 dollar, and they were obliged to come and repair the house, thus involving local businesses and giving working places to the locals. I think it is an ideal scheme. And it worked! It attracted a lot of artists to come, both American and international.

We were invited to the residency for one of the programs, the main aim of which was to communicate with the local community. When we arrived, we realized that it was absolutely not the America you see on TV, in Washington, New York or other big cities. Oksana was shooting the artists who lived and worked in these buildings. And I, as usual, wanted to do something with history. I found out that on this territory took place the Civil War and the segregation.

Once I went to an antique shop. Well, they called it an antique shop, but basically it was a junk shop. There I saw these metal tintypes and thought: ‘Damn, they’re amazing!’. It is important to say that in the second half of the 19th century this type of early photography was so popular that soon it turned into market photography and spread in the whole country. The images were wrapped into a paper cover, on the back of which they put advertisement. Photography turned into business. The photographers were advertising their studios called after themselves – ‘Jordan Brothers’, for example, - cool names of that time, old American ones.

“Far superior to Photographs: American tintype”, New Wing Art Space, The House of Gogol, Moscow, Russia, 2020

When I saw on one of the tintypes the advertisement ‘Get your image in only seven minutes’ – for me it became kind of an early Polaroid. I bought all the old portrait tintypes across the local shops and with a modern Polaroid camera shot the landscapes and the houses. This way I superimposed the people who were alive back then and the places that exist now. In parallel, I was searching for objects of that time: barbed wire of Civil War or an old lipstick which we noticed in a flooded cinema theatre Columbia, which still had a floor for whites and another one for blacks. When you get into this town, you realize that it is as if frozen in time.

When we came back, I started searching for various tintypes and buying them on the auctions, junk shops, in a trip to USA and on the internet. I was searching for them in different states in order to see all the life of that time.

The guys from the museum (Gogol House New Wing), with who we made the war exhibition, asked me: ‘Do you have any other interesting archive?’. Right away I showed them my findings, and we decided to make another exhibition.

In the result it occupies six rooms. The last of them is for the project I did in Paducah. The other five are played out differently to let the viewer do kind of a time travel: we show the technology, which objects there were and what the photographers were doing; then we do a Sander’s typology with an Americanist who could provide at least some description of these tintypes: estimated year, the class of the people in the images, their profession. We made a separate room for these typologies which allow to see how people looked like, what did they do for living, how different classes dressed.

In another room we project the reverse plen aire effect: while the artists used to go out on the street, make a draft, then come back to the studio and finish the painting, the photographer gradually went out from the studio on the street and started to interact with it. One can say it was the rise of photojournalism: the cameras still had long exposure standing on a tripod, not allowing to take a quick picture and keep going like nowadays, but you can already see how the photographers started to select the stories, up to the first appearances of landscapes with nothing, no houses, no humans. You cannot recognize the timepoint on such landscape, it is a contemplation landscape, which later on becomes a separate genre in American photography.

“Far superior to Photographs: American tintype”, New Wing Art Space, The House of Gogol, Moscow, Russia, 2020

How do you search and how do you understand that you have found something valuable? What is the percentage of what you reject out of what you buy? What do you do later with the unnecessary archives? How much on average do you spend on them?

These are good questions. I will start from the latter: I spend almost 95% of my earnings. Taking the good and bad catches as percentage, basically when buying an archive that you have never seen in reality, you never know what you are getting. A seller might display one good image, and in the end you buy 90% of useless rubbish, and only this one picture is good. Sometimes a seller might not understand the value and just display the whole lot, and I understand myself that there is interesting content. Since I work a lot with film, usually I can understand by the preview how good is the shot. Also, I search for any writings and notes, because eventually it turns into an investigation, and thanks to the writings or other small details I learn a lot about the archive.

Regarding how precisely I know what I buy – almost never. What do I do with unnecessary archives? If I realize that I do not need the photos at all, I just throw them away. For example, I bought some images – Germany, family archive, but there is almost nothing apart from the fact that this archive was shot five years before the war. So, I just throwed it away. Going through every archive takes a lot of time, so I do not waste it for no reason. Even though it was quite expensive, I would not resell it. For me it is just a waste of time, which year by year I have less. I have a feeling that the time is shrinking so fast that I just do not manage to do and grasp everything. I have a lot of archives: if now I stop buying them, for a couple of years I will be just going through what I have. It is not because of being greedy of having extra money.

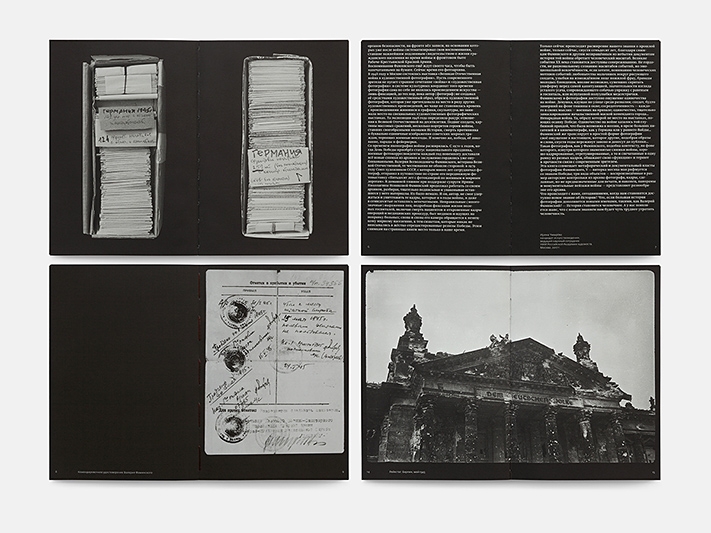

I think that now is an important period, and I can say surely that it is coming to an end. You can see it by how often war archives appear in pawn shops or the auctions – today they are very few. In 2016 I bought the first archive by Faminsky (Valeriy Faminskiy – a soviet photojournalist). Four years passed, and there are no archives anymore.

It was a borderline time when the new generation came; the third generation which was not directly related to the war, which almost did not have any grandparents who had gone through the war. They do not have this personal connection to the past; that is why they say goodbye to these things so easily: either throw them away or gift to someone; or somebody moves in a place, finds them and takes to a pawn shop.

Recently I received a hand-made archive of a Hero of the Soviet Union. His relatives told me: ‘We don’t really want to keep it, but throwing it away feels bad, so we want to give it to someone’. So, I told them: ‘Well, give it to me’. All that considering that the person is a Hero of the Soviet Union. I think this happens to many people, especially if there is no personal communication, or maybe someone thinks it is not important. But for me it is very important. After all, it is history that unites us. It is an international history which you can tell in any country and it will be understood.

While working with the archives, it is important to understand that apart from the films, you need to keep all the little papers and envelopes, because they often tell the city where it was taken; or the street where the studio was; or the owner of this studio; or the customer. Sometimes it is like this: I have some rolls – it is an archive of a German obstetrician. The Germans are very meticulous, and they have right on the metal cassettes, on the rolls a sticker: what, where, when (with the address of his clinic). So, any materials are useful, because they give a key to the later decryption of the archive.

Then you check the images: read the notes, look at the architecture, sometimes you can even read the names of the streets. If you cannot determine the location, check the uniform. Try to understand who it is: a motorcyclist or a rider, an artillery man, a marine or a pilot. The specialists in World War II machines help a lot. Later you try to determine the unit where the person served, at which time period – it is a collection of pieces of history. So, buying an archive is just 25% of the work.

Visual archaeology, Norway / 1940

Artur, you said you had a large archive collection which would be enough for two years of work. Do you collect some specific archives: of a certain time or a certain topic?

The tintypes are just a side story which I manage when there is a chance, I do not hunt them specifically. I search for the war time negatives because I am particularly interested in the World War II, so not just the Great Patriotic War, but the years ftom 1939 to 1945, +\- a couple of years before and after. For example, the Beatles archives are of little interest for me, as well as the soviet archives of the 70s-80s.

I think there is a lot of historians working with famous archives. I am interested, first of all, in the unknown war archives, made both by professional photographers and amateur soldiers and simple civilians – usual family archives.

Do you have any taboo topics in relation to the archives?

To be honest, no, but for me the biggest tragedy is that the World War II archives will soon disappear without a trace. Why is the World War II topic specifically important for me? Because I see how this topic is manipulated in Russia, Ukraine, Poland, Belarus – when the real witnesses go, this issue is very easy to pull from one side to another. Why do I consider very important the activity of the search teams looking for the missing soldiers? Because the main goal is to bring the soldier back to the family. The common graves are a great instrument belonging to the government. As soon as the person returns to the family, they belong to the family and no longer can be a tool of manipulation.

In the future, if everything goes well, I have an idea to make a unified platform, to publish all the material so that the person who enters it can see how, for example, Poland was represented in photography by the Germans when they occupied it, and later how the soviet soldiers pictured it when they came to liberate Poland. Or how Ukraine or Belarus were shot during the German attack, and how it was captured by the soviet photojournalists. I am interested to provide the opportunity to look at the same time period, the same territory from two sides, and the person can make their own conclusion.

Have you had problems with the archives after publishing them? Have you had issues with the previous owners or the relatives of the people on the photos?

For example, in case of Famisnky’s archive, his granddaughter found this archive on the internet after the publication. If I buy an archive personally, we make an agreement of alienation of property, commercial and non-commercial rights. It is for a good reason, since the money is quite a lot. I cannot disclose it, but for example the price for Famisnky’s archive is comparable to a car. I sold all the copies of the Chernobyl book and for that amount bought the Faminsky’s archive, to add to the question about how much I spend on the archives.

Archive of Valery Faminsky, photo book by Arthur Bondar

We have the main question: what advice can you give to the young photographers, maybe to those who are planning to also work with the archives?

First of all, to be engaged and not have people around you who would be telling you it is impossible: impossible to find the archives; impossible to make a project; impossible to publish a book. Everything is possible if you want it enough!

Arthur Bondar

Pop quiz

The most valuable advice from your grandparents?

- From my grandmother: with lies you can walk the whole planet, but never come back.

What is the question you would like to answer, but nobody ever asks?

- It is a difficult question. I don’t think there are such questions. Everything I would ask myself about, I already have been asked. Mostly it is the same question: Why?

Tell us about your favourite place?

- Well, there are several of them, not one; at least two. The first one is the place where I grew up and which does not exist anymore, the military town. The second one is Balaklava (Crimea), where we got together with my wife Oksana.

Finish the sentence: modern art is …

- Modern art is not about money.

What morning exercise do you do?

- I do the brain exercise before sleeping.

site